- Home

- Paul Langan

Brothers in Arms Page 3

Brothers in Arms Read online

Page 3

I hated that Frankie was right. My mother moved us to the other side of the city. To get back home, I had to take a fifty-minute stop-and-go trip by bus, one I’d have to pay for. There was no getting around it; I was stuck.

I hung up the phone and started walking. Anything to pass the time. You can only watch so much TV in the middle of the day before you start to really go crazy.

The new neighborhood was completely different from back home. For one thing, there were black people everywhere, old and young, on the street. Where I came from, almost everyone was Chicano or Mexican. We had blacks in a few houses, but we didn’t really hang out with them, and they didn’t hang with us. That was just the rule, and no one said anything.

It’s the same with the white people. They didn’t live anywhere near us, and they always seemed scared when they made a wrong turn and ended up on my street. But they weren’t scared when they were looking for a Mexican housekeeper or someone to take care of their yard, pick their vegetables. To them, we were all the same, even though my mom was a third generation American. She hardly ever speaks Spanish. I don’t even know it, except for a few words.

Some day, if I ever get a house with a yard, I want to hire white people to cut my grass. Just because.

Besides blacks, I saw a little shop owned by what I guessed were Chinese people. Then there was a pizza shop called Niko’s. Those people were white, but they weren’t speaking a language I knew.

Down the busiest street near my place, I found a restaurant that looked kind of nice called the Golden Grill. All the cars parked in the lot were nice and new. No lowriders with chrome rims and booming systems. I wasn’t impressed.

Not far from the Golden Grill was an ice cream stand called Scoops. A pretty white girl with blond hair was working in there. I nodded at her as she cleaned the front window, but she ignored me. It’s all good, though. Blond girls aren’t my type.

I turned up another street, and quickly the vibe of the neighborhood changed. The houses were squeezed closer together, and broke-down cars lined the street. Some of the homes had iron bars on the windows and doors. Others were rundown and in need of paint. A stop sign on the corner had been spray painted with a tag I didn’t recognize. The word “Stop” had been covered in silver paint, and beneath it someone had written the word “Go”.

Two black kids in baggy jeans checked me out as I walked.

“Wassup,” one boy said. He was standing on the corner, wearing a black warm-up jacket. The hood was pulled up loosely over his head, though it was warm out. He looked to be my age.

“’Sup,” I said. I had lived in the city long enough to know you didn’t move through other people’s blocks unless you knew where you were going and what you were doing. And if you didn’t know those things, you acted like you did. So I moved to the next corner like it was the place I wanted to go. Then I turned back to the main street. I ain’t saying I was scared. I’m just not stupid, and these streets were new to me.

I went back toward the pizza place and asked an old woman how to get to Bluford High School. She had a bag full of groceries, and she gave me this you-look-dangerous face.

Please! I thought. I ain’t about to hurt an old woman.

I couldn’t get mad at her, though. Me and my boys got that look whenever we went anywhere as a group. One time Frankie asked a guy on a street corner the time, and the man looked at us and said, “I don’t have any money. ” Like Frankie was gonna steal his wallet or something! Still, when people start treating you like you’re a criminal, you start believing you are one. If that guy had given Frankie some money, I bet he would have kept it. I know he would.

Back in the day, I took a kid’s bike once when I found it lying unprotected outside. And one time, Chago and I stole the stereo out of a car that had been left unlocked. But that was two years ago, long before Huero got shot. I was a different person then. Even though we did those things, none of us would just go up and rob a person. Especially not an old lady. That’s just low.

I smiled at the woman so she’d know I wasn’t there to hurt her. My smile these days is weak, but it worked. After a ten-minute walk following her directions, I was standing in front of my new prison away from home, Bluford High School.

The school was just past a grocery market. On the one side of the lot were some houses and a small park. On the other side, sitting in a ring of protective fence, was Bluford. Made of brick and cement, it looked like a giant fortress.

You could fit two Zamora High schools inside Bluford. It was that big. Behind the school was an outdoor track which circled a full-sized football field. Grey metal bleachers were on either side, and I could see a huge sign in blue and yellow letters: Home of the Bluford Buccaneers.

The sign made my stomach feel queasy, the way it gets when you eat too much fast food. I knew the school year was about to begin. I’d heard the dumb back-to-school commercials on the radio, but seeing the sign over the football field made it more real.

I’m not going to lie to you. I hate school. It started in fourth grade when my teacher, Ms. Simon, failed me.

“Martin has attention and behavioral problems,” she said with a voice that came more through her nose than her mouth.

What Ms. Simon didn’t know was that was just before my dad left, when he was drinking and hitting my mom. Ma would never admit something like that to anyone, especially my teacher, so I just had to repeat my grade. After that, people started treating me like I was stupid, and I stopped taking school seriously. My mom, and even my dad for a time, were always strict about me trying my best, but I gave that up long ago. Instead, I just coasted, hung out, got by, and waited for summer. But with Huero’s death, school seemed pointless. A bad joke.

I was thinking all this when a security guard approached me from inside the fence.

“You late for practice, young man?” the guard yelled to me. “You can still get in if you go around front. ”

Behind him, I could see a few students stepping out onto the football field.

“Na, I’m cool,” I said, turning away, trying not to laugh in the guard’s face. I had no time for high school football, coaches, players, the whole bit. That’s just not me.

And neither was Bluford.

The morning of my first day at Bluford High School, my mom looked at me with her eyes glowing and hopeful. Like it was my first day of kindergarten, not tenth grade. It took all my strength not to get on a bus home.

“You’re going to start fresh here, mijo. No more gangs. ”

“Yes, Ma. ”

“Try to make me and Huero proud,” she said, giving me a kiss. Her eyes were dripping again. I knew the tears were for Huero, not me.

“I will, Ma,” I said, turning away from her and thinking ahead to the day me and Frankie would catch that shooter.

“And try to start coming to church again. It’s been too long since you were there, mijo. ”

“Okay, Ma. ”

Good thing she couldn’t hear my eyes rolling in my head.

Bluford was a maze of hallways with freshmen running back and forth like cats in an alley. I was new too, but I wasn’t about to run around like that. Instead, I just acted like I was with my homeboys, taking my time to get to where I was supposed to be.

I wore the saggiest jeans I had, a white T-shirt, and white high tops. I put the gold cross around my neck under my shirt, and I cut my hair short, Caesar-style. My look always blended right in at Zamora. At Bluford, I was sure I’d stand out, but I didn’t care. I was too cool to rush, too angry to worry. I didn’t want to be there, and I wanted the whole world to know it.

I arrived late to my classes. It was the first day, so my first two teachers didn’t seem to mind. But then I went to my third period class, English.

“You are all sophomores now, so I expect you to be on time every day,” the teacher said, as I walked in five minutes late. The teacher, a light-skinned black man in a shirt the color of Frankie’s car, had his back to me.

I stopped and shrug

ged, looking for a desk. My timing was perfect.

A couple students chuckled, and a pretty girl with wavy black hair flashed me a great smile. I scratched my chin, trying to look cool.

“Excuse me, Mr. Mitchell, sir, but you have a guest,” said a guy in the third row. He had a muscular build and a wide grin on his face. I could tell right away that I didn’t like him.

“Thank you, Steve,” Mr. Mitchell said, turning to me. “Can I help you?”

“Yeah, I think I belong in this class,” I said. Twenty-five sets of eyes scanned me like I was for sale. I met their eyes until some of them looked away.

“Are you Martin Luna?” he said, checking a list on his desk. “A transfer student from Zamora High School?”

“Yeah. ” Some students giggled at the name of my high school.

“Good. You’re in the right place. Now, Martin. You’re late,” he said with a weird smile. I wasn’t sure if he was mad or not, and I was distracted by his tie. It was bright red and had a picture of a cartoon character. Tweety Bird, I think.

“I had locker trouble,” I said quickly, an excuse that always works in the beginning of the school year.

Mr. Mitchell nodded for a second as if he was thinking about what I said. Yet he was looking at me the whole time, like his eyes were magnifying glasses. “Well, just don’t have locker trouble tomorrow. Go ahead and grab a seat. ”

I heard a few whispers as I made my way to the back row on the left side of the room. I liked sitting in the back where I could see the entire classroom. Plus, it’s the best place to be when you don’t do your homework.

The girl with the dark hair was only one row in front and over from me. From my seat, I could see her long hair stretching all the way to the middle of her back.

“Well, Martin, welcome to our class and to Bluford High. I’m Mr. Mitchell, and as I just said to your classmates, I expect you to show up on time unless there is a serious reason for you not to be here. Got it?” he said.

I nodded, scratching my chin.

“Is sleep a serious reason, ’cause I’m tired this early in the morning,” said a kid in the back row on the opposite side of the room. I could tell he was trying to be funny, but I thought his joke was weak, even though several students chuckled.

“Roylin, that’s ’cause you spent all summer messing up on the football field,” said Steve, laughing at his own joke.

“Shut up, Morris,” Roylin said, looking annoyed.

“Unless you two want to continue this discussion after school this week, I suggest you both pay attention,” Mr. Mitchell said. “We’ve got lots of work to do. ”

“Absolutely, Mr. Mitchell,” Steve said, a smile on his face stretching from ear to ear. He was the kind of kid who always had the last word, the kind of kid I couldn’t stand.

I leaned back in my chair and zoned out. I saw Mr. Mitchell pass back some papers and watched as kids started reading, but my mind drifted to Huero and then to my homeboys. I wondered how Frankie and the boys were doing back home. I imagined Huero on his first day of kindergarten several years ago. He was so scared, my mom had to walk him onto the bus. After a few days, school became his favorite place.

“What do you think, Martin?” I heard Mr. Mitchell say, his voice snapped me out of my daydream.

“Huh?” I had no clue what was going on. Somewhere thirty minutes had disappeared.

“Wake up, dude,” Steve said.

“Based on the story we just read, and what you’ve seen in your life, what do you think makes a person a hero?” Mr. Mitchell asked. I could tell from his voice that he was repeating the question. I could also see that he knew I hadn’t been paying attention.

I tried to think quickly. I had no idea what the story was about, and the question annoyed me. “I don’t know any heroes. ” I said. “And if I did, I wouldn’t trust ’em. ”

Mr. Mitchell nodded. “Anybody want to help Martin?”

“A hero is strong and tough,” Steve said. “Someone who doesn’t back down. ”

“Good, Steve, but are all strong people heroes?” Mr. Mitchell challenged, even as he wrote Steve’s words on the chalkboard.

Then the long-haired girl with the great smile raised her hand. “I think a hero is someone who does the right thing, even if it means she might get in trouble. Like someone who stands up for people who aren’t strong like Steve. ”

Some students laughed. I liked her answer.

“Very nice, Vicky,” Mr. Mitchell said, jotting her answer under Steve’s. “So are you saying a hero is someone who must take an action?” he asked, his eyes twinkling. “Can you give me an example?”

Just then, the bell rang.

“Saved by the bell,” Mr. Mitchell said. “We’ll talk more about this tomorrow. Your assignment tonight is to write a paragraph about a person who is a hero to you. Try to give details about this person so readers will understand. It’s not going to be graded yet, so don’t worry. Just write. ”

I couldn’t believe it. Homework. At Zamora, I skipped it about half the time, but I could see that Mr. Mitchell wouldn’t let me get away with that.

“Remember, Martin. Be on time tomorrow,” he said as I walked out.

I bit my tongue. Me and that teacher were definitely going to have problems. I knew it.

Vicky was in front of me as I headed into the crowded hallway. She was talking to another girl from our class.

“Teresa, why did I ever go out with Steve?” Vicky said. “He’s such a jerk. ”

“He’s not that bad,” Teresa said.

I laughed quietly as I passed Vicky. At least there was one thing about Bluford that I liked.

Chapter 4

The rest of my first day at Bluford dragged like Frankie’s first car, an old Chevette with a half-blown engine. U.S. history with Mrs. Eckerly was boring, though I met a funny kid named Cooper. Algebra II with Mr. Singh was even worse. By the time I got to biology with Mrs. Reed, I was ready to go home.

After study hall where I listened to a snobby girl named Brisana gossip about a weekend party, I went to my last class, Phys. Ed. with Mr. Dooling. I was tired when I finally found the gym. But as soon as I entered the locker room, I spotted Steve Morris. He was giving a high-five to a kid next to him. With his shirt off, I could see he had an athlete’s body. Much bigger than me or any of my boys.

“Can you believe that, Clarence?” he said. “One day soon I’m gonna pop Roylin. ”

“Man, you’d kill him,” Clarence said.

“Yeah, but until football season ends, I gotta stay out of trouble. Coach would kick me off the team. ” I noticed everyone in that section of the locker room was quiet, as if Steve was someone special.

Inside the gym, Mr. Dooling, an older man who looked as tired as me, took attendance and assigned our class to break into groups to play basketball. I admit it. Basketball isn’t my sport, and I ain’t no LeBron James. So I hung on the sidelines with a couple other kids and watched Steve strut out onto the court.

“Who wants to play me?” he challenged, bouncing a ball hard against the gym floor.

Once the game started, he was an animal on the court, stealing the ball and blocking shots. None of the other guys could touch him. I watched one kid, smaller and quicker than the others, try to defend the basket. The kid’s arms were out, his feet were planted, but Steve just charged through him as if he wasn’t there. Up went Steve’s lay-up while the other guy went smashing to the ground like he’d been hit by a train.

“That’s what I’m talking about,” Steve boasted, punching his chest. Clarence slapped Steve’s hand in triumph.

The other kid lay on the wooden floor holding his head for several seconds before he slowly got up, his feet unsteady. The whole scene just rubbed me the wrong way.

“Easy, Morris. This isn’t football,” Mr. Dooling warned.

“If it was, he wouldn’t be getting up,” Steve bragged.

Back in the locker room, Steve kept talking about his basketball ga

me.

“Man, did you see that kid fly? That felt good,” he said.

“Steve, you crushed him. He’s gonna think twice next time he steps on the court with you,” Clarence said. He seemed to follow Steve like a dog looking for scraps.

I tried to ignore them as I waited in line to leave, but then Steve described how he hit the kid. “I was like WHAP,” he said performing his hit and then laughing about it. Clarence chuckled with him.

Maybe it was because I was tired.

Maybe it was because I hated Bluford, or maybe it was because I missed Huero, and something about seeing that kid on the ground bothered me. I’m not sure. All I know is that I suddenly couldn’t take listening to Steve.

“Man, how many times you gonna keep telling us what you did?” I said. “It don’t take that much skill to hit someone who’s half your size. ”

A couple kids standing next to me moved away, and Clarence looked a little stunned, as if he’d never heard someone speak the truth to him before.

“Do I know you?” Steve asked, sizing me up.

“You do now,” I said.

“You’re that loser from Zamora who’s in my English class, aren’t you?”

“Nah, you’re that punk from Bluford in my English class,” I said, taking a step forward.

Steve’s eyes narrowed.

I dropped my books. I wanted my hands free, just in case.

Was I dangerous? Was I a gangbanger? That’s what he was thinking. Though he didn’t say it, I could see it in his face. He wasn’t sure about me.

The bell signaling the end of the day sounded, and kids started rushing out.

“Come on, Steve. We gotta go to practice,” Clarence said.

“You and me are gonna continue this later, Sanchez,” Steve said.

“I hope so,” I said, eyeing him until he turned the corner.

“That was cool,” said a short kid behind me in the locker room. I almost laughed.

Frankie and the boys would be proud.

“How was your day, mijo?” my mother asked when she got home. She looked tired. I knew the move increased her own commute to work. She was home an hour later than usual.

The Fallen

The Fallen Summer of Secrets

Summer of Secrets Brothers in Arms

Brothers in Arms The Gun

The Gun Blood is Thicker

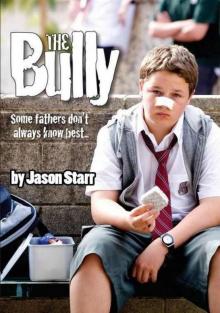

Blood is Thicker The Bully

The Bully